Screening for Occult Factor VIII Deficiency in Prospective Blood Donors in South-South Nigeria

| Received 03 Aug, 2025 |

Accepted 10 Oct, 2025 |

Published 31 Dec, 2025 |

Background and Objective: Factor VIII and IX play pivotal roles in the coagulation cascade, essential for blood clotting. In health, these clotting factors act in concert to ensure effective haemostasis. The aim was to investigate the activity levels of factor VIII and IX of Prospective blood donors attending the Blood Donor Bay, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, Nigeria. Materials and Methods: This was a cohort study design of 50 subjects, adult males and females, aged 15 to 45 years. Micro-haematocrit method for Hct was tested for recruitment, and Quick’s One Stage Method using Helena Biosciences Europe Factor Deficient Plasmas in APTT-based Factor Assay Testing was used for APTT, FVIII, and FIX. Results were expressed as Mean±S.D, and analyzed using Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA, and Pearson correlation, with significance set at p<0.05. Results: The majority of donors were male (88%) and students (76%), with most aged 26-35 years (46%) and the fewest aged 36-45 years (10%); non-alcohol consumers made up 66% and alcohol consumers 34%, while first-, second-, and third-time donors accounted for 66, 20, and 14% respectively, with no statistically significant influence (p>0.05) of age, gender, donation frequency, or alcohol use on factor VIII and IX activity. The Mean±SD of Hct, APTT, FVIII, and FIX of prospective Blood Donors was 0.418L/L, 30 sec, 80.0 and 90.7%. The factor VIII and IX activity levels were 92% and 100%, respectively in the normal (Non-Haemophilia range) of 50-150% factor activity. Meanwhile, only factor VIII revealed 2% each in Near-Normal (Non-Haemophilia range) and Mild Haemophilia of >40%-<50% and >5%-<40%, respectively. The male donors have the highest factor VIII and IX activity levels 80.6 and 90.9% to the female 77.0% and 89.2%. For alcohol consumers, there was a statistical difference in APTT (<0.044) when compared with non-alcoholic. There was no correlation between FVIII and FIX activity levels vs. APTT (p<0.001). Conclusion: This study has shown Near-Normal (non-haemophilia range) and mild haemophilia of factor VIII among blood donors. However, an adequate activity level of factor IX was seen in all blood donors. Therefore, assessing factor VIII and FIX activity levels of blood donors should be used as a criterion to assess and know donors who have adequate and efficient replacement therapy for patient with medical issues.

| Copyright © 2025 Okpokam et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

Blood donation plays a crucial role in healthcare, providing a lifeline for patients in need of transfusions due to various medical conditions or emergencies. To ensure the safety and effectiveness of blood transfusions, it is essential to understand the prevalence of specific factors present in the blood, such as factor VIII1. Haemostasis is the physiological process by which bleeding is stopped and blood vessels are repaired after an injury2. Blood clotting is a complex process involving a series of interactions among various clotting factors3.

Factor VIII and factor IX are essential proteins in the blood coagulation cascade, which is critical for maintaining haemostasis. Factor VIII is a glycoprotein that acts as a cofactor for factor IX, enhancing its ability to activate factor X, leading to the formation of a blood clot4. These proteins play a pivotal role in the intrinsic pathway of coagulation, and deficiencies in either factor VIII or IX lead to haemophilia, a genetic disorder that impairs the blood’s ability to clot5.

In Nigeria, the incidence of haemophilia, particularly Haemophilia A (caused by factor VIII deficiency) and Haemophilia B (caused by factor IX deficiency), is significant yet underreported. It is estimated that Nigeria has a prevalence of haemophilia similar to global figures, but due to limited diagnostic facilities and awareness, many cases remain undiagnosed or misdiagnosed6. The burden of haemophilia in Nigeria is further exacerbated by challenges in accessing adequate treatment and care, leading to increased morbidity and mortality among affected individuals6.

Haemophilia is a hereditary bleeding disorder, primarily affecting males, characterized by spontaneous or prolonged bleeding, particularly into joints and muscles. Haemophilia A and B are X-linked recessive disorders, meaning that they predominantly affect males, while females are typically carriers4. The severity of haemophilia depends on the level of factor VIII or IX activity in the blood, with severe cases resulting in frequent bleeding episodes. In Nigeria, managing haemophilia poses significant challenges due to limited healthcare resources, lack of specialized treatment centers, and the high cost of clotting factor concentrates, which are essential for effective management6. The study aimed to investigate the activity levels of factors VIII and IX among prospective blood donors at the Blood Donor Bay, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area: A cohort study was carried out among blood donors coming to the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar Nigeria. The study site was Blood Donor Bay, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, which serves as a primary health care provider and referral centre, catering for the medical needs of the local population and surrounding regions. The study was conducted over nine months, from June, 2023 to February, 2024.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar (UCTH), Health Research Ethical Committee (HREC) with Reg. Number: NHREC/07/10/2012 and HREC Protocol assigned Number: UCTH/HREC/33/Vol.III/147 Permission to enrol candidates was sought and obtained from all participants through informed consent and a questionnaire. To be eligible for inclusion, donors met the following criteria: Both male and female volunteers who gave informed consent were included in this study; commercial donors, walk-in donors, autologous donors, and family replacement donors. Those who did not give consent were excluded from the study.

Sample collection and preparation: A total of 4.5 mL of blood was collected aseptically from a prominent vein using a plastic syringe and dispensed into 0.5 mL of 3.13% trisodium citrate anticoagulant bottle. The sample was gently but adequately mixed with the anticoagulant to avoid the slightest clot.

The sample and the anticoagulant were in the ratio of 9:1, and it was centrifuged at 1500g for 15 min to obtain platelet-poor plasma for factor VIII and IX assay immediately after the collection. The plasma separated was transferred into a sterile plain plastic bottle and then labeled. Plasma was kept at 2-8°C and testing was completed within 4 hrs of sample collection, sometimes stored frozen at -20°C for 2 weeks. It was thawed quickly at 37°C before testing and was not kept at 37°C for more than 5 min. Micro-haematocrit method for Hct was tested for recruitment, and Quick’s One Stage Method using Helena Biosciences Europe Factor Deficient Plasmas in APTT-based Factor Assay Testing was used for APTT, FVIII, and FIX. A calibration graph was prepared and in turn the % activity of patient plasma was determined.

Factor VIII and IX activity level

Principle: A dilution of the test plasma is mixed with the factor-deficient plasma, and the clot time of the mixture is determined. The degree of clot time correction with the patient plasma is compared to the correction with a reference material, allowing the % activity of the patient plasma to be determined.

| Tube | Calibration plasma (mL) (REF 5185) | Owren’s buffer (mL) (REF 5375) | Activity (%) |

| 1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 100 |

| 2 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 50 |

| 3 | 0.1 | 1.9 | 25 |

| 4 | 0.1 | 3.9 | 12.5 |

Procedure

| • | 1 in 4 dilution of the patient plasma or control plasma in Owren’s buffer was prepared | |

| • | It was mixed without shaking | |

| • | 0.1 mL of factor suspected plasma was pipette into a reaction tube | |

| • | 0.1 mL of APTT Si L minus reagent was added and incubated for 5 min at 37°C | |

| • | 0.1 mL of 0.025 M calcium chloride solution was added while simultaneously a stopwatch was started | |

| • | Clot time for each of the standard, control or patient dilutions was determined | |

| • | A graph of % activity (X-axis) versus mean clot Time (Y-axis) for the standard on 2 cycle log-log paper was plotted | |

| • | A straight line graph was obtained |

Data analysis: Results are presented in tables as Mean+Standard Deviation (S.D), student t-test, ANOVA and Pearson correlation were used for the analysis of data. Pearson correlation and one-way ANOVA were used to compare means. A p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

This study was carried out to show the demographics of the blood donors recruited at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital Donor Bay (Table 1). It shows information on 50 blood donors, with their ages ranging from 15-25, 26-35, and 36-45. The age ranges of blood donors show that 15-25 (44%) and 26-35 (46%) while 36-45 had the lowest percentage (10%). The male shows a higher percentage (88%), and the female shows a percentage of 12%. In 3 months during which the research was carried out, the occupations with the highest representation were the students (76%), traders (12%), unemployed (4%), entrepreneurs (4%), health worker (2%), and security staff (2%). In response to the questionnaire administered, the percentage of the Efik tribe (44%) which shows the highest, followed by Tiv (22%), Igbo (20%), Ibibio (6%), Yoruba (6%), and Urhobo (2%) with the lowest percentage. Thirty-six (72%) of the blood donors engaged in regular exercise, while 14 (28%) did not. Ten percent were smokers, while ninety percent of them had never smoked. Also, 34% of the blood donors were alcohol consumers, while 66% had never or rarely taken any alcoholic product. Zero percent of the donors live in a high altitude (five-storey building and above), and also zero percent have any occupational hazard (exposure to harsh chemicals, massive electric shock, and exposure to radioactive substances). From the questionnaire administered, 66% of the donors were first-time donors, second-time donors (20%) and third-time donors (14%). More so, only 22% are aware of the potential impact of factor VIII levels on blood donation, while 78% are oblivious.

| Table 1: | Demographic data and health history of blood donors attending University of Calabar Teaching Hospital | |||

| Demographics Age range (years) |

Number n=50 | Frequency (%) |

| 15-25 | 22 | 44 |

| 26-35 | 23 | 46 |

| 36-45 | 5 | 10 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 44 | 88 |

| Female | 6 | 12 |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 38 | 76 |

| Trader | 6 | 12 |

| Entrepreneur | 2 | 4 |

| Unemployed | 2 | 4 |

| Health worker | 1 | 2 |

| Security | 1 | 2 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Efik | 22 | 44 |

| Tiv | 11 | 22 |

| Igbo | 10 | 20 |

| Ibibio | 3 | 6 |

| Yoruba | 3 | 6 |

| Urhobo | 1 | 2 |

| Lifestyle factors | ||

| Exercise | ||

| Yes | 36 | 72 |

| No | 14 | 28 |

| Smokers | ||

| Yes | 5 | 10 |

| No | 45 | 90 |

| Alcohol consumers | ||

| Yes | 17 | 34 |

| No | 33 | 66 |

| Environmental factors | ||

| Are you exposed to any occupational hazard? | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 50 | 100 |

| High altitude | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0 |

| No | 50 | 100 |

| Blood donation history | ||

| Have you ever donated blood? | ||

| Yes | 17 | 34 |

| No | 33 | 66 |

| Frequency of donation | ||

| First time | 33 | 66 |

| Second time | 10 | 20 |

| Third time | 7 | 14 |

| Knowledge and awareness | ||

| Are you aware of the potential impact of factor VIII levels on blood donation eligibility? | ||

| Yes | 11 | 22 |

| No | 39 | 78 |

Table 2 shows the Mean±SD of Hct, APTT, factor VIII, and factor IX activity level of blood donors. The Mean±SD of Hct, APTT, FVIII, and FIX activity level of blood donors was 0.418L/L±2.75, 29.7 sec±6.41, 80.0%±13.6, and 90.7%±11.3, showing the overall average of the parameters utilized in this study.

| Table 2: | Mean±SD of parameters used | |||

| Parameters | Mean±SD |

| Hct (L/L) | O.418±2.75 |

| APTT (sec) | 29.7±6.41 |

| Factor VIII (%) | 80.0±13.6 |

| Factor IX (%) | 90.7±11.3 |

| Table 3: | Factor VIII and FIX activity levels of blood Donors according to the WFH guideline | |||

| Classification | Factor VIII activity of blood donors (n=50) |

Factor IX activity of blood donors (n=50) |

| Normal (Non-haemophilia range) | 48 (92%) | 50 (100%) |

| 50%-150% factor activity | ||

| Near-normal (Non-haemophilia range) | 1(2%) | - |

| >140%-<50% factor activity | ||

| Mild haemophilia | 1(2%) | - |

| >5%-<40% factor activity | ||

| Moderate haemophilia | - | - |

| >1%-5% factor activity | ||

| Severe haemophilia <1% factor activity | - | - |

| Classification of haemophilia according to the World Federation of Haemophilia (WFH) guideline7 | ||

| Table 4: | Factor VIII and IX activity levels, Hct, and APTT levels of blood donors based on age | |||

| Parameters | 15-25 years (n=22) | 26-35 years (n=23) | 36-45 years (n=5) | p-value |

| Hct (L/L) | 0.415±2.95 | 0.423±2.54 | 0.414±2.97 | 0.587 |

| APTT (sec) | 31.23±5.03 | 28.69±7.75 | 27.20±3.70 | 0.282 |

| FVIII activity level (%) | 79.50±10.68 | 81.00±16.53 | 79.40±4.97 | 0.924 |

| FIX activity level (%) | 90.4±8.81 | 90.9±14.38 | 90.8±3.03 | 0.985 |

| Values are expressed as One-way ANOVA values, p<0.05 are statistically significant, APTT: Activated partial thromboplastin time, Hct: Haematocrit, FVIII: Factor VIII activity level assay and FIX: Factor IX activity level assay | ||||

| Table 5: | Factor VIII and FIX activity levels, Hct and APTT of blood donors based on gender | |||

| Parameters | Males (n=44) | Females (n = 6) | p-value |

| Hct (L/L) | 0.42 ±2.49 | 0.38±1.60 | 0.255 |

| APTT (sec) | 29.34±6.56 | 32.00±5.01 | 0.611 |

| Factor VIII activity level (%) | 80.61±13.79 | 77.00±7.48 | 0.858 |

| FIX activity level (%) | 90.8±11.96 | 89.2±3.37 | 0.089 |

| Values are expressed as t-test values p<0.001 are statistically significant, APTT: Activated partial thromboplastin time, Hct: Haematocrit, FVIII: Factor VIII activity level assay and FIX: Factor IX activity level assay | |||

According to the classification of Haemophilia guideline established by the World Federation of Haemophilia (WFH) revealed in Table 3 as follows, normal (Non-Haemophilia Range) 50-150% factor activity, near-normal (Non-Haemophilia Range) >140%-<50% factor activity, mild haemophilia >5%-<40% factor activity, moderate haemophilia >1%-5% factor activity, severe haemophilia <1% factor activity. It was observed that 1 (2%) of the male blood donors exhibit near-normal (Non-Haemophilia Range) of ≥140%-≤50% factor activity and mild haemophilia of >5%-<40% of factor VIII activity level only, respectively, and thus classified under them.

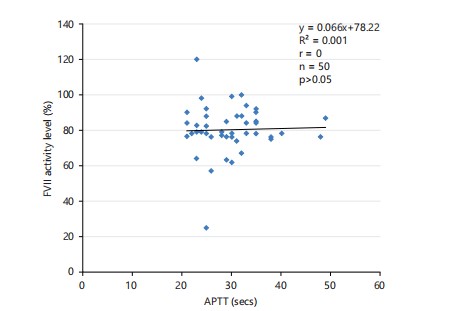

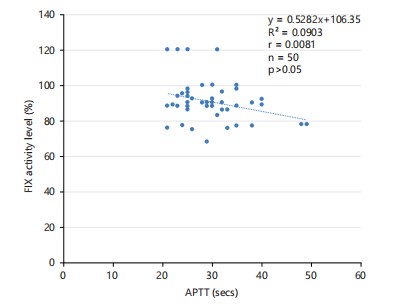

Table 4 shows Hct, APTT, factor VIII, and activity levels of blood donors based on age range. The Mean±SD of Hct, APTT, and FVIII activity level of blood donors aged 15-25 years was (0.415L/L±2.95, 31.23 sec±5.03, 79.50%±10.68, and 90.4%±8.81), 26-35 years (0.423L/L±2.54, 28.69 sec±7.75, 81.00%±16.53, and 90.9%±14.4) and 36-45 years (0.414L/L±2.97, 27.20 sec±3.70, 79.40%±4.97, and 90.8%±3.03), respectively. This shows that there was no significant difference (p>0.05) in the age range. Table 5 shows Hct, APTT, and factor VIII activity level of blood donors based on gender. In Hct, male was (0.42L/L ±2.49 and female 0.38L/L±1.60), APTT was (29.34 sec±6.56 and 32.00 sec±5.01), FVIII activity level (80.61%±13.79 and 77.00%±7.48), and FIX activity level was (90.8%±11.9 and 89.2%±3.37). It was observed that there was a significant difference (p>0.05). Table 6 shows Hct, APTT, and FVIII activity level of blood donors based on frequency of donation. In Hct, APTT, and FVIII activity level of first-time donors were (0.41L/L±2.64, 29.57 sec±5.36, 79.72±14.88, and 90.6±9.79), second-time donors (0.41L/L±1.88, 29.20 sec±7.75, 79.90%±11.23, and 87.4%±10.0), and third-time donors (0.42L/L±4.18, 30.71sec±9.49, 82.71%±6.55, and 95.7%±18.0), respectively. It shows that there was no significant difference (p>0.05). Table 7 shows Hct, APTT, and FVIII activity level of blood donors based on alcohol intake. There was a significant decrease (p<0.05) in APTT parameters of blood donors on alcoholic intake (28.29 sec±8.58) than those not on alcohol (30.36 sec±4.96). Hct, FVIII, and FIX activity levels show no significant difference (p>0.05) in alcoholics and non-alcoholics (0.42L/L±3.32 and 0.41L/L±2.43), (81.29%±7.74 and 79.60±15.35), and (90.7%±13.3 and 90.7%±10.3), respectively. Correlation graphs between APTT versus FVIII and APTT versus FIX activity levels of blood donors were shown in Fig. 1-2. It was observed that there was no significant (r=0, p>0.05, r=0.0081, p>0.05) correlation between APTT vs FVIII and APTT vs FIX activity levels in the study.

|

|

| Table 6: | Factor VIII and FIX activity levels, Hct and APTT of blood donors based on frequency of donation | |||

| Parameters | First time donors (n=33) | Second time donors (n=10) | Third time donors (n=7) | p-value |

| Hct (L/L) | 0.41±2.64 | 0.41±1.88 | 0.42±4.18 | 0.568 |

| APTT (sec) | 29.57±5.36 | 29.20±7.75 | 30.71±9.49 | 0.888 |

| Factor VIII activity level (%) | 79.72±14.88 | 79.90±11.23 | 82.71±6.55 | 0.865 |

| FIX activity level (%) | 90.6±9.79 | 87.4±10.0 | 95.7±18.0 | 0.332 |

| Values are expressed as one way ANOVA values, p<0.05 are statistically significant, APTT: Activated partial thromboplastin time, Hct: Haematocrit, FVIII: Factor VIII activity level assay and FIX: Factor IX activity level assay | ||||

| Table 1: | Factor VIII and FIX activity levels, Hct and APTT of blood donors based on alcohol intake | |||

| Parameters | Alcoholics (n=17) | Non alcoholics (n=33) | p-values |

| Hct (L/L) | 0.42±3.32 | 0.41±2.43 | 0.531 |

| APTT (sec) | 28.29±8.58 | 30.36±4.96 | 0.044* |

| Factor VIII activity level (%) | 81.29±7.74 | 79.60±15.35 | 0.216 |

| FIX activity level (%) | 90.7±10.25 | 90.6±13.30 | 0.491 |

| Values are expressed as t-test values p<0.001 are statistically significant, APTT: Activated partial thromboplastin time, Hct: Haematocrit, FVIII: Factor VIII activity level assay and FIX: Factor IX activity level assay | |||

DISCUSSION

Among the 50 donors utilized in this study, it was observed that the students donated blood more frequently, followed by traders and entrepreneurs. The reason the student donated more was that there is always a strong voluntary blood donation drive targeted at the student, while traders and entrepreneurs do it for pecuniary benefit. The mean age showed that most donors are mainly young people who are less than 35 years. According to the American Red Cross, in 2020, approximately 4.3 million blood donations were collected in the United States of America, which is enough to save over 1.3 million lives7,8. This equates to around 1.7% of the population compared to Nigeria, which is less than 1%, according to the National Blood Transfusion Service (NBTS) in 2018. Most of the population in the United States of America has been enlightened on the importance of donation, which makes almost the age range eligible to participate. This is in line with research conducted in UCTH, which reported that the majority of blood donors were within the same age range. This finding is a reflection of the demographic structure of Nigeria, a developing country characterized by a young population9,10.

The findings of this study indicate that factor VIII and IX activity levels in prospective blood donors attending the Blood Donor Bay, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, were within the normal haemostatic range (50-150%). This aligns with previous studies conducted in Nigeria and other parts of the world. A study in South-West Nigeria similarly reported normal FVIII and FIX levels among blood donors, reinforcing the reliability of donor screening protocols in maintaining haemostatic integrity11,12. Furthermore, studies in Italy also demonstrated comparable FVIII and FIX ranges among healthy donors, indicating that geographical and genetic variations have minimal impact on these factors in healthy individuals13. However, the observation of a small proportion of donors with mild haemophilia or near-normal factor VIII levels suggests that routine assessment of coagulation factors could be crucial in donor selection, as also recommended by Mahlangu et al.14in a study on coagulation screening in West African blood banks. Interestingly, the study found that male donors had slightly higher FVIII and FIX activity levels than females, a trend also observed in Nigeria and in Egypt, respectively15,16. These differences may be attributed to hormonal influences on coagulation factors, particularly the effect of estrogen in reducing FVIII levels in females.

It was also interesting to observe that 34% of donors consume alcohol regularly even before donation, while 66% do not consume any alcohol product. It was discovered that blood donors in UCTH who are alcohol consumers and non-alcohol consumers had mean values of 81.2 and 79.6% respectively. The Hct and factor VIII activity level based on frequency of donation have no significant difference but there was a statistical difference in APTT (<0.044). This is in line with research conducted in Imo State, which showed that alcohol consumption hurts the APTT values of an individual17. According to the National Blood Transfusion Service18, the recommended timeframe for abstaining from alcohol before blood donation is 48 hrs. Additionally, the significant difference in APTT among alcohol consumers supports

previous findings by Schmölders et al.19 in India, which reported prolonged APTT in chronic alcohol users, likely due to alcohol-induced hepatic dysfunction affecting coagulation proteins. However, contrary to these results, a study in the United States found no significant APTT alterations in moderate alcohol consumers, suggesting that the effects of alcohol on coagulation may depend on drinking patterns and underlying genetic factors20. This is consistent with the international guidelines, which are based on the fact that alcohol can impair platelet function and increase the risk of bleeding complications during and after surgery, yet little or no donor was deferred. Studies have shown that alcohol consumption is relatively common among blood donors in Nigeria and other parts of Africa, although their exact prevalence may vary depending on the specific location21.

Moreover, the absence of correlation between FVIII and FIX activity levels and APTT (p<0.001) contradicts the general expectation that lower clotting factor levels would lead to prolonged APTT, as demonstrated in studies by Do et al.22 in Nigeria and Kwon et al.23 in Spain. This discrepancy could be due to the insensitivity of APTT to detect mild factor deficiencies or compensatory mechanisms within the coagulation cascade that maintain clotting efficiency despite variations in FVIII and FIX levels. This finding underscores the need for advanced coagulation assays, such as thrombin generation tests, to accurately assess haemostatic potential in blood donors, as recommended by Lim et al.24. Future studies with larger sample sizes and additional haemostatic markers could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the implications of FVIII and FIX variations in prospective donors.

CONCLUSION

This study found that factor VIII and IX activity levels among prospective blood donors at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital were within the normal haemostatic range, with only a small percentage showing near-normal or mild haemophilia FVIII levels. Male donors had slightly higher factor levels than females, and alcohol consumption significantly affected APTT. However, the lack of correlation between FVIII, FIX, and APTT highlights the limitations of routine clotting tests in detecting mild factor deficiencies. These findings emphasize the need for improved screening methods and further research to enhance donor selection and transfusion safety. Blood banks should consider incorporating FVIII and FIX activity assessments, particularly for donors with a history of bleeding tendencies, to enhance transfusion safety. Larger cohort studies should explore the genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors influencing FVIII and FIX levels in different populations to refine donor selection criteria.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

This study provides crucial insight into the activity levels of clotting factors VIII and IX among prospective blood donors in Calabar, Nigeria. By identifying near-normal and mild haemophilia ranges in some individuals, particularly with reduced factor VIII activity, this research underscores the need for more comprehensive pre-donation screening beyond routine haematological tests. These findings have implications for blood transfusion safety and for ensuring that patients requiring factor replacement therapy receive blood components with adequate clotting factor levels. This study supports the inclusion of factor VIII and IX screening in donor evaluation protocols, contributing to enhanced clinical outcomes and transfusion practices in haemostatic disorder management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the staff and management of the Blood Donor Bay, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, for granting access to their facilities and the assistance provided during sample collection and analysis. We are especially grateful to all the blood donors who volunteered to participate in this study. We also appreciate the technical support from Helena Biosciences Europe and the Laboratory Scientists who contributed to the successful completion of this work.

REFERENCES

- WHO, 2021. Global Status Report on Blood Safety and Availability 2021. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, ISBN: 9789240051683, Pages: 172.

- Green, D., 1978. Haemostasis: Biochemistry, physiology, and pathology. JAMA, 239: 1327-1328.

- Scridon, A., 2022. Platelets and their role in hemostasis and thrombosis-From physiology to pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 23.

- Larsen, J.B. and A.M. Hvas, 2021. Thrombin: A pivotal player in hemostasis and beyond. Semin. Thromb. Hemostasis, 47: 759-774.

- Srivastava, A., E. Santagostino, A. Dougall, S. Kitchen and M. Sutherland et al., 2020. WFH guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia, 26: 1-158.

- Ndoumba-Mintya, A., Y.L. Diallo, T.C. Tayou and D.N. Mbanya, 2023. Optimizing haemophilia care in resource-limited countries: Current challenges and future prospects. J. Blood Med., 14: 141-146.

- Graw, J., H.H. Brackmann, J. Oldenburg, R. Schneppenheim, M. Spannagl and R. Schwaab, 2005. Haemophilia A: From mutation analysis to new therapies. Nat. Rev. Genet., 6: 488-501.

- Twarog, J.P., A.T. Russo, T.C. McElroy, E. Peraj, M.P. McGrath and A.C. Davidow, 2019. Blood donation rates in the United States 1999-2016: From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). J. Am. Board Fam. Med., 32: 746-748.

- Chioma, O.D., O.E. Efiom, U.E. Achibong, E.A. Uchenna and E.A. Ogbonna, 2018. Correlation between soluble transferrin receptor versus haemoglobin concentration, transferrin saturation and serum ferritin levels following repeated blood donations in Nigeria. Asian J. Biol. Sci., 11: 9-15.

- Okpokam, D.C., E.E. Osim and E.A. Usanga, 2019. Effect of pecuniary benefit on some haematological and iron-related parameters of blood donations: A study at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital Blood Donor Clinic, Calabar, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci., 19: 803-810.

- Momodu, I., S. Abdulkadir, I.S. Yahaya and E. Osaro, 2018. Assessment of some haematological and biochemical parameters of family replacement blood donors in Gusau, Nigeria. Open Access Blood Res. Tranfus. J., 2.

- Ogar, C.O., D.C. Okpokam, H.U. Okoroiwu and I.M. Okafor, 2022. Comparative analysis of hematological parameters of first-time and repeat blood donors: Experience of a blood bank in Southern Nigeria. Hematol. Transfus. Cell Ther., 44: 512-518.

- Bowyer, A.E. and R.C. Gosselin, 2023. Factor VIII and factor IX activity measurements for hemophilia diagnosis and related treatments. Semin. Thromb. Hemostasis, 49: 609-620.

- Mahlangu, J., K. Shikuku and L.G. Dogara, 2019. Capacity building for inherited bleeding disorders in Sub-Saharan Africa. Blood Adv., 3: 5-7.

- Wang, Z., M. Dou, X. Du, L. Ma and P. Sun et al., 2017. Influences of ABO blood group, age and gender on plasma coagulation factor VIII, fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS13 levels in a Chinese population. PeerJ, 5.

- Afifi, O.A.H., E.M.N. Abdelsalam, A.A.E.A.M. Makhlouf and M.A.M. Ibrahim, 2019. Evaluation of coagulation factors activity in different types of plasma preparations. Indian J. Hematol. Blood Tranfus., 35: 551-556.

- Ifeanyi, O.E., O.H. Mercy, C.C.N. Vincent and O.H.C. Henr, 2020. The effect of alcohol on some coagulation factors of alcoholics in Owerri, Imo State. Ann. Clin. Lab. Res., 8.

- Ogbenna, A., S.A. Adewoyin, C.O. Famuyiwa, K.M. Oyewole, O.A. Oyedeji and A.S. Akanmu, 2021. Pattern of blood donation and transfusion transmissible infections in a hospital-based blood transfusion service in Lagos, Nigeria. West Afr. J. Med., 38: 1088-1094.

- Schmölders, R.S., T. Hoffmann, D. Hermsen, M. Bernhard, F. Boege, M. Lau and B. Hartung, 2025. Evaluation of alcohol intoxication on primary and secondary haemostasis-results from comprehensive coagulation testing. Int. J. Legal Med., 139: 1797-1808.

- Mukamal, K.J., P.P. Jadhav, R.B. D’Agostino, J.M. Massaro and M.A. Mittleman et al., 2001. Alcohol consumption and hemostatic factors: Analysis of the framingham offspring cohort. Circulation, 104: 1367-1373.

- Obekpa, I.O., P.E. Agbo, A.M. Amedu and S.A. Itodo, 2024. Prevalence and determinants of alcohol use in Benue South Senatorial District, Nigeria. Eur. J. Med. Health Res., 2: 120-126.

- Do, L., E. Favaloro and L. Pasalic, 2022. An analysis of the sensitivity of the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) assay, as used in a large laboratory network, to coagulation factor deficiencies. Am. J. Clin. Pathol., 158: 132-141.

- Kwon, E.H., B.K. Koo, S.H. Bang, H.J. Kim and Y.K. Cho, 2015. Analysis of coagulation factor activity of normal adults with APTT limit range. Korean J. Clin. Lab. Sci., 47: 237-242.

- Lim, H.Y., G. Donnan, H. Nandurkar and P. Ho, 2022. Global coagulation assays in hypercoagulable states. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis, 54: 132-144.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Okpokam,

D.C., Iji,

M.O., Nwaeze,

V.C., Bassey,

B.O., Akaba,

K.O., Ogidi,

N.O., Okpokam,

O.E. (2025). Screening for Occult Factor VIII Deficiency in Prospective Blood Donors in South-South Nigeria. Trends in Pharmacology and Toxicology, 1(2), 127-136. https://doi.org/10.21124/tpt.2025.127.136

ACS Style

Okpokam,

D.C.; Iji,

M.O.; Nwaeze,

V.C.; Bassey,

B.O.; Akaba,

K.O.; Ogidi,

N.O.; Okpokam,

O.E. Screening for Occult Factor VIII Deficiency in Prospective Blood Donors in South-South Nigeria. Trends Pharm. Toxicol. 2025, 1, 127-136. https://doi.org/10.21124/tpt.2025.127.136

AMA Style

Okpokam

DC, Iji

MO, Nwaeze

VC, Bassey

BO, Akaba

KO, Ogidi

NO, Okpokam

OE. Screening for Occult Factor VIII Deficiency in Prospective Blood Donors in South-South Nigeria. Trends in Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2025; 1(2): 127-136. https://doi.org/10.21124/tpt.2025.127.136

Chicago/Turabian Style

Okpokam, Dorathy, Chioma, Moses Onahi Iji, Victory Chidiebere Nwaeze, Bassey Okon Bassey, Kingsley Onoriode Akaba, Nkeiruka Ogo Ogidi, and Ogha Eyamnzie Okpokam.

2025. "Screening for Occult Factor VIII Deficiency in Prospective Blood Donors in South-South Nigeria" Trends in Pharmacology and Toxicology 1, no. 2: 127-136. https://doi.org/10.21124/tpt.2025.127.136

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.