Antitrypanosomal Activity and Safety Evaluation of Ficus capensis Leaf Extracts in Mice Infected with Trypanosoma brucei

| Received 17 Aug, 2025 |

Accepted 10 Oct, 2025 |

Published 31 Dec, 2025 |

Background and Objective: African trypanosomiasis, caused by Trypanosoma brucei, remains a major health concern in Sub-Saharan Africa, with increasing drug resistance highlighting the need for new therapeutic agents. Ficus capensis, a medicinal plant used in African traditional medicine, has demonstrated various pharmacological properties, including antiprotozoal activity. This study aimed to evaluate the antitrypanosomal efficacy and safety of different solvent extracts of Ficus capensis leaves in a mouse model infected with T. brucei brucei. Materials and Methods: Male mice were infected with T. brucei brucei and treated with aqueous, methanol, dichloromethane, or cyclohexane leaf extracts of F. capensis at doses of 50, 100, and 150 mg/kg. Parasitemia levels and survival times were recorded. Acute toxicity was assessed up to 3000 mg/kg. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, and significance was determined at p<0.05. Results: The methanol extract exhibited the highest antitrypanosomal activity, significantly reducing parasitemia and extending survival up to six days (p<0.05). Other extracts showed limited efficacy, with treated mice surviving no longer than four days. Toxicity testing revealed no adverse effects across all extracts at doses up to 3000 mg/kg. Conclusion: Ficus capensis, particularly its methanol leaf extract, demonstrates promising antitrypanosomal activity with a favorable safety profile. These findings support its potential as a source of alternative therapeutic agents against African trypanosomiasis, warranting further studies to isolate active compounds and optimize treatment efficacy.

| Copyright © 2025 Musa et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. |

INTRODUCTION

African trypanosomiasis, caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Trypanosoma. Trypanosoma brucei brucei is primarily responsible for African animal trypanosomiasis (AAT), a life-threatening disease and a major threat to livestock in Sub-Saharan Africa, causing economic losses exceeding US$4.5 billion annually1. The parasite has potential for zoonotic transmission to humans, especially in cases involving Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense or Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, leading to Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) or sleeping sickness2. The disease, endemic in at least 37 African countries, is transmitted by the tsetse fly (Glossina spp.) and, if left untreated, can lead to severe neurological complications and death3,4.

Current treatment options for trypanosomiasis include pentamidine, suramin, melarsoprol, eflornithine, nifurtimox, and the recently approved oral drug fexinidazole5-7. However, they are limited by issues of toxicity, side effects, limited efficacy, high costs and emerging resistance6-8. Consequently, the need for new, cost-effective, antitrypanosomal solutions is driving interest in natural products like medicinal plants, which have demonstrated antimicrobial properties in African ethnomedicine.

Medicinal plants offer a rich source of bioactive compounds, and Ficus capensis is widely used in traditional medicine across West Africa for the treatment of various ailments, including parasitic infections9. Previous studies have identified several bioactive compounds in Ficus capensis, such as flavonoids, tannins, and alkaloids, which possess antimicrobial and antiprotozoal activities10,11. Despite the traditional use of Ficus capensis in treating different diseases, and in vitro studies demonstrating its potential as an antimicrobial agent12, in vivo evaluations of its antitrypanosomal efficacy remain sparse. Therefore, this study aimed to address this gap by examining the efficacy and safety of different solvent extracts of Ficus capensis leaves in mice infected with Trypanosoma brucei.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area and duration: This study took place in Nigeria from May, 2021 through October, 2021. Ficus capensis leaves were collected in May, 2021 from Olamaboro Local Government Area, Kogi State, Nigeria (7°11'N, 7°34'E). Extraction and phytochemical procedures were carried out in the Department of Biochemistry, Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University, Lapai, Niger State, Nigeria.

Plant material collection and preparation of extracts: Leaves of Ficus capensis were collected from Kogi State, Nigeria, and identified by botanists at Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University, Lapai, Nigeria. The leaves were air-dried, pulverized, and sequentially extracted using cyclohexane, dichloromethane, methanol, and water. Two hundred grams of the pulverized leaf sample was sequentially macerated in 900 mL of each solvent for 24 hrs, with intermittent stirring, followed by filtration using Whatman No. 1 filter paper. The filtrates were concentrated using a rotary evaporator at 40°C to avoid degradation of the bioactive compounds. The concentrated extracts were reconstituted in normal saline for aqueous extracts and in cold-pressed olive oil for non-polar extracts before administration to animals.

Experimental animals and grouping: Adult albino mice of both sexes, weighing between 27-30 g, were obtained from the National Institute for Trypanosomiasis Research, Kaduna, Nigeria. The mice were acclimatized for two weeks under standard laboratory conditions with a 12 hrs light/dark cycle. The mice were provided with water and standard rodent feed ad libitum and maintained on a 12 hrs light/dark cycle. The experimental protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida University.

The mice were randomly divided into fifteen groups (n = 3 per group):

| • | Group 1: Infected, untreated (negative control) | |

| • | Group 2: Infected, treated with 150 mg/kg of aqueous extract | |

| • | Group 3: Infected, treated with 100 mg/kg of aqueous extract | |

| • | Group 4: Infected, treated with 50 mg/kg of aqueous extract | |

| • | Group 5: Infected, treated with 150 mg/kg of methanol extract | |

| • | Group 6: Infected, treated with 100 mg/kg of methanol extract | |

| • | Group 7: Infected, treated with 50 mg/kg of methanol extract | |

| • | Group 8: Infected, treated with 150 mg/kg of dichloromethane extract | |

| • | Group 9: Infected, treated with 100 mg/kg of dichloromethane extract | |

| • | Group 10: Infected, treated with 50 mg/kg of dichloromethane extract | |

| • | Group 11: Infected, treated with 150 mg/kg of cyclohexane extract | |

| • | Group 12: Infected, treated with 100 mg/kg of cyclohexane extract | |

| • | Group 13: Infected, treated with 50 mg/kg of cyclohexane extract | |

| • | Group 14: Infected, treated with standard trypanocidal drug (positive control) | |

| • | Group 15: Non-infected, non-treated (normal control) |

The treatments were administered intraperitoneally once daily for six days. Mice were monitored for behavioral changes and survival time was recorded.

Parasite inoculation and parasitemia monitoring: Trypanosoma brucei parasites were obtained from the Vector and Parasitology Department, National Institute for Trypanosomiasis Research, Kaduna, Nigeria. The parasites were passaged in a donor mouse, and the parasites were maintained in the laboratory by continuous passage in mice. For the experiment, each mouse was inoculated intraperitoneally with 0.2 mL of infected blood in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing approximately 1×104 trypanosomes.

Parasitemia levels were monitored every two days by obtaining blood samples from the tail vein, which were then smeared on glass slides, stained with Giemsa, and examined under a light microscope at ×40 magnification. Parasite load was estimated using the Rapid Matching method13, which involves comparing the number of parasites per field to a standard chart.

Acute toxicity studies: The evaluation of the acute toxicity of the extracts was carried out using the fixed-dose method14. Twenty mice of the same gender were randomly assigned to four groups, and each group received an intraperitoneal injection of a predetermined fixed dose of 2000 mg/kg of a distinct extract (aqueous, methanol, dichloromethane, and cyclohexane). The mice were closely monitored for 24 hrs following administration for signs of toxicity, such as changes in behavior and physical condition, including motor coordination, convulsions, lacrimation, piloerection, and salivation, as well as mortality. If no adverse effects were observed, the mice received an additional dose of 3000 mg/kg, and their condition was monitored for another 48 hrs. After the observation period, the mice were humanely euthanized, and their major organs (liver, kidneys, lungs, heart, and spleen) were examined for any notable gross pathological changes.

Statistical analysis: Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. The results were reported as Mean±Standard Deviation. The statistical software used for this analysis was SPSS version 22.0.

RESULTS

Yield: Extraction yields varied markedly, with the aqueous extract yielding the highest (2%), followed by methanol (0.7%), dichloromethane (0.4%), and cyclohexane (0.3%).

Antitrypanosomal activity: The assessment of the antitrypanosomal activity of Ficus capensis leaf extracts was conducted by evaluating the parasitemia levels and survival times of infected mice. The normal, uninfected control animals survived the entire experiment. The negative control group, which was infected but not treated, exhibited the highest parasitemia levels and the shortest survival time of only two days. In contrast, the positive control group, which received the standard drug treatment, demonstrated an effective suppression of parasitemia.

The results of the study did not show any significant difference (p>0.05) in the mean concentration of trypanosomes among the three groups administered with the aqueous leaf extract of Ficus capensis, as shown in Table 1. Similarly, there was no significant difference (p>0.05) in the mean survival duration, as all mice that received the aqueous extract perished four days after inoculation, as indicated in Table 1.

| Table 1: | Anti-trypanosomal effects of aqueous leaf extract of Ficus capensis | |||

| Treatment doses (mg/kg) | Mean trypanosome count per field | Mean survival time (days) |

| 150 | 13.7±4.5bc | 4b |

| 100 | 22.7±8.7c | 4b |

| 50 | 7.67±6.4b | 4b |

| Control | 36.0±1.2d | 2a |

| Standard drug (3.5) | 0.0±0.0a | 9c |

| Trypanosome counts are given as Mean±Standard Deviation. In each column, values with the same superscripts have no significant difference (p>0.05) | ||

| Table 2: | Anti-trypanosomal effects of methanol leaf extract of Ficus capensis | |||

| Mean trypanosome count per field | |||

| Treatment doses (mg/kg) | D2 | D4 | Mean survival time (days) |

| 150 | 6.0±5.3b | 41.3±9.5b | 6b |

| 100 | 7.67±6.4b | 49.7±13b | 6b |

| 50 | 14.0±5.7b | 50.5±12b | 6b |

| Control | 36.0±1.2c | Dead | 2a |

| Standard drug (3.5) | 0.0±0.0a | 0.0±0.0a | 9c |

| Trypanosome counts are given as Mean±Standard Deviation. In each column, values with the same superscripts have no significant difference (p>0.05) | |||

| Table 3: | Anti-trypanosomal effects of dichloromethane leaf extract of Ficus capensis | |||

| Treatment doses (mg/kg) | Mean trypanosome count per field | Mean survival time (days) |

| 150 | 15.0±5.0b | 4b |

| 100 | 12.0±4.0b | 4b |

| 50 | 11.7±7.6b | 4b |

| Control | 36.0±1.2c | 2a |

| Standard drug (3.5) | 0.0±0.0a | 9c |

| Trypanosome counts are given as Mean±Standard Deviation. In each column, values with the same superscripts have no significant difference (p>0.05) | ||

| Table 4: | Anti-trypanosomal effects of cyclohexane leaf extract of Ficus capensis | |||

| Treatment doses (mg/kg) | Mean trypanosome count per field | Mean survival time (days) |

| 150 | 68.0±5.7d | 4b |

| 100 | 11.0±6.6b | 4b |

| 50 | 16.3±12b | 4b |

| Control | 36.0±1.2c | 2a |

| Standard drug (3.5) | 0.0±0.0a | 9c |

| Trypanosome counts are given as Mean±Standard Deviation. In each column, values with the same superscripts have no significant difference (p>0.05) | ||

The mean survival time of the mice administered with different doses of the methanol leaf extract of Ficus capensis was six days post-inoculation, as indicated in Table 2. No significant difference (p>0.05) was observed in the mean survival time among the three dosage groups (50, 100, and 150 mg/kg). Furthermore, there was no significant difference (p>0.05) in the mean trypanosome count across the three dosage groups on both day two and day four post-inoculation, as shown in Table 2.

According to Table 3, there was no significant difference (p>0.05) in the mean trypanosome count among the mice that received 50, 100, and 150 mg/kg of the dichloromethane leaf extract of Ficus capensis. Furthermore, there was no significant variation in the mean survival time across the treatment groups, as all mice died on the fourth day post-inoculation.

The survival time of the mice treated with the cyclohexane extract had a mean of four days post-inoculation, with no variation observed among the three dosage groups (p>0.05) (Table 4). However, a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) in the mean trypanosome count was noted on day two post-inoculation. Mice treated with 150 mg/kg of the extract exhibited a higher parasitemia level compared to those treated with either 50 or 100 mg/kg of the extract (Table 4). Additionally, no significant difference (p>0.05) in the mean trypanosome count was observed between the 50 and 100 mg/kg treatment groups (Table 4).

|

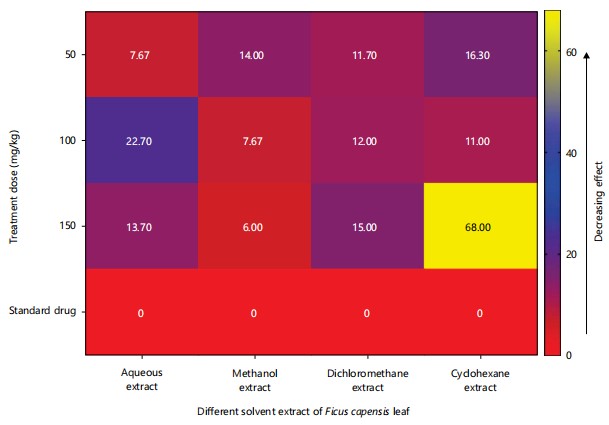

The heatmap (Fig. 1) illustrates the antitrypanosomal effects of the Ficus capensis leaf extracts. Among the extracts, the methanol extract demonstrated the highest efficacy, particularly at the 150 mg/kg dose, where it reduced parasitemia to 6 trypanosomes/μL compared to 7.67 trypanosomes/μL at 100 mg/kg and 14 trypanosomes/μL at 50 mg/kg. In contrast, the aqueous extract showed limited efficacy across all doses, with the highest parasitemia observed at 100 mg/kg (22.7 trypanosomes/μL). The dichloromethane and cyclohexane extracts exhibited moderate to low efficacy, with the cyclohexane extract at 150 mg/kg showing the highest parasitemia (68 trypanosomes/μL). Notably, the standard drug treatment was the most effective, with no detectable parasitemia.

At a 50 mg/kg dose, the aqueous extract had the lowest mean trypanosome count (7.67±6.4), followed by the dichloromethane extract (11.7±7.6) and the cyclohexane extract (16.3±12). The methanol extract’s mean count (14.0±5.7) was higher than the aqueous and dichloromethane extracts but lower than the cyclohexane extract. There were no significant differences (p>0.05) between the extracts at this dose. The control group had the highest parasitemia (36.0±1.2), whereas the standard drug reduced the count to 0.0±0.0 (Fig. 1).

At 100 mg/kg, the methanol extract had a mean trypanosome count of 7.67±6.4, not significantly different (p>0.05) from the dichloromethane (12.0±4.0) and cyclohexane extracts (11.0±6.6). The aqueous extract showed the highest count (22.7±8.7) among the solvent extracts, significantly higher (p<0.05) than the other extracts at this dose.

At 150 mg/kg, the methanol extract had the lowest count (6.0±5.3), significantly lower (p<0.05) than the cyclohexane (68.0±5.7) and dichloromethane extracts (15.0±5.0). The aqueous extract also had low parasitemia (13.7±4.5), comparable to the dichloromethane extract but significantly lower than the cyclohexane extract (p<0.05).

Acute toxicity: The acute toxicity study revealed that all extracts were well-tolerated up to 3000 mg/kg, with no mortality or significant signs of toxicity observed. Post-mortem examinations of the liver, kidneys, lungs, heart, and spleen showed no gross pathological changes, indicating that the extracts were non-toxic at the doses tested.

DISCUSSION

The extraction yields obtained from Ficus capensis leaves varied significantly across different solvents, suggesting that solvent polarity affects the extraction yields of bioactive compounds from plant material. The higher yield from the aqueous extract is likely due to the greater solubility of a broad range of polar compounds in water15. Aqueous extractions recover various phytochemicals, including tannins, flavonoids, and glycosides, which are abundant in Ficus capensis11. Conversely, the cyclohexane extract, being non-polar, yielded the least amount, possibly because it primarily extracted non-polar compounds, present in lower concentrations in the plant material16,17.

The heatmap analysis (Fig. 1) provides a clear visual representation of the differential efficacy of the Ficus capensis extracts. The methanol extract’s significant reduction in parasitemia, particularly at the 150 mg/kg dose, highlights its potential as a potent antitrypanosomal agent. Methanol has proven to be an effective solvent for extracting bioactive compounds from various plant sources. Studies have shown that methanol extracts yield high concentrations of phenols, flavonoids, tannins, and alkaloids18,19, which have been reported to possess antiprotozoal activities12. The absence of a clear dose-dependent effect suggests that the effective compounds are potent even at lower concentrations, which is advantageous for therapeutic applications, and agrees with Bero et al.20 suggested that effective compounds can induce significant enzymatic activity without a typical dose-response relationship.

The aqueous extract, despite yielding a high amount, demonstrated a limited capacity for antitrypanosomal activity. This may result from the presence of compounds that, while abundant, exhibit less effectiveness against Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Alternatively, the aqueous extract may possess a combination of bioactive and inactive or even antagonistic compounds, which could diminish its overall efficacy. The results of previous studies by Oloruntola et al.21 and Obeng et al.22 align with the viewpoint that polar organic solvent extracts display superior antitrypanosomal activity when compared to aqueous extracts, which may be attributed to the higher concentration of flavonoids and alkaloids. However, the findings of Atawodi23 contradict this as their report suggests that the aqueous extract of Tetrapleura tetraptera fruit exhibits significant antitrypanosomal activity, while the ethanol extracts only show moderate activity.

The efficacy of the dichloromethane and cyclohexane extracts was found to be moderate to low, with the cyclohexane extract performing the least at the highest dose. The poor performance of the cyclohexane extract can be attributed to its non-polar nature, which limits the extraction of polar bioactive compounds that are effective against Trypanosoma brucei brucei. This finding is not consistent with old study of Nibret and Wink24, which found that less polar solvent extracts were more effective than methanol and aqueous extracts in eliminating trypanosome motility, and another study of Mbaya et al.25 reports that dichloromethane extracts generally showed moderate to high efficacy, with several plants exhibiting IC50 values below 20 μg/mL. The significantly higher parasitemia observed at the 150 mg/kg dose of the cyclohexane extract may indicate a potential adverse interaction or toxicity that exacerbates the infection, a phenomenon that suggests that the use of natural products for treating trypanosomiasis may be associated with both promising results and potential risks26. Higher doses of plant extracts can lead to toxicity. An in silico study of antitrypanosomal natural products revealed that certain compounds may bind to nuclear receptors, potentially causing endocrine disruption, while others may inhibit cytochrome P450 enzymes, leading to drug-drug interactions27.

The high parasitemia levels observed in untreated mice infected with Trypanosoma brucei brucei underscore the lethal nature of the infection. By the second day, there was 100% mortality of all animals in this group, which is consistent with the findings of Ibrahim et al.28, reported that parasitemia levels can reach as high as 10.8×107 trypanosomes/mL in untreated mice, leading to 0% survival by the third day post-infection. The results of the extracts, in contrast to the standard drug (which showed complete suppression of parasitemia), indicate the lack of effective antitrypanosomal activity of the extracts in their natural form. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which have suggested that their effectiveness is generally inferior to that of standard drugs29.

The results of acute toxicity tests indicate that Ficus capensis extracts are well-tolerated up to a dose of 3000 mg/kg, which provides initial evidence for their safety. The absence of visible pathological changes in vital organs suggests that these concentrations have a non-toxic profile. This conclusion is consistent with the findings of Eluka et al.30, which reported that the chloroform extract of Ficus capensis had an LD50 of >5000 mg/kg body weight in albino rats. Similarly, Ibe et al.31 reported that acute toxicity tests revealed no toxicity up to a dose of 5000 mg/kg in rats. This is significant because it establishes a wide therapeutic window for Ficus capensis extracts, particularly the methanol extract, which displayed the highest efficacy. The absence of toxicity at high doses also suggests that the active compounds are likely to be safe for therapeutic use, provided that further studies are conducted on chronic toxicity and long-term effects.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this research indicate that the methanol extract of Ficus capensis exhibits moderate antitrypanosomal activity, which is evidenced by its ability to reduce parasitemia levels and extend the survival of infected mice. However, the efficacy of this extract is limited in comparison to the standard trypanocidal drug. The aqueous, dichloromethane, and cyclohexane extracts demonstrated less effectiveness against Trypanosoma brucei brucei. The favorable safety profile observed in acute toxicity studies suggests that the methanol extract of Ficus capensis may be a safe antitrypanosomal agent, which warrants further investigation to optimize its therapeutic potential as a viable alternative treatment for trypanosomiasis.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT

African trypanosomiasis, commonly known as sleeping sickness, poses a significant threat to livestock and human health across Sub-Saharan Africa. Current treatments can be toxic, expensive, and less effective as the parasite evolves. This study investigated whether leaves from Ficus capensis, a West African tree traditionally used in folk medicine, could provide a safer and more affordable alternative. In this study, infected mice were treated with the methanol leaf extract from Ficus capensis. The results showed a reduction in parasite levels, and the treated mice lived six days longer than untreated ones, effectively tripling their survival time. Notably, even at high doses, the extract did not cause harm to the mice. However, water-based and non-polar extracts were less effective. These findings suggest that Ficus capensis contains active compounds that combat the parasite without causing immediate side effects. Further research is needed to isolate and refine these beneficial molecules, which could lead to affordable new treatments. Such advancements would help protect livestock, support rural incomes, and reduce the risk of human infection, thereby improving both food security and public health in affected regions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge our colleague, Mr. Abduljelil Uthman, for his technical support during the laboratory work of this research.

REFERENCES

- Yaro, M., K.A. Munyard, M.J. Stear and D.M. Groth, 2016. Combatting African animal trypanosomiasis (AAT) in livestock: The potential role of trypanotolerance. Vet. Parasitol., 225: 43-52.

- Papagni, R., R. Novara, M.L. Minardi, L. Frallonardo and G.G. Panico et al., 2023. Human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness): Current knowledge and future challenges. Front. Trop. Dis., 4.

- Bonnet, J., C. Boudot and B. Courtioux, 2015. Overview of the diagnostic methods used in the field for human African trypanosomiasis: What could change in the next years? Biomed Res. Int., 2015.

- Muhanguzi, D., A. Mugenyi, G. Bigirwa, M. Kamusiime and A. Kitibwa et al., 2017. African animal trypanosomiasis as a constraint to livestock health and production in Karamoja Region: A detailed qualitative and quantitative assessment. BMC Vet. Res., 13.

- Imran, M., S.A. Khan, M.K. Alshammari, A.M. Alqahtani and T.A. Alanazi et al., 2022. Discovery, development, inventions and patent review of fexinidazole: The first all-oral therapy for human African trypanosomiasis. Pharmaceuticals, 15.

- Jamabo, M., M. Mahlalela, A.L. Edkins and A. Boshoff, 2023. Tackling sleeping sickness: Current and promising therapeutics and treatment strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 24.

- Melfi, F., S. Carradori, C. Campestre, E. Haloci, A. Ammazzalorso, R. Grande and I. D’Agostino. 2023. Emerging compounds and therapeutic strategies to treat infections from Trypanosoma brucei: An overhaul of the last 5-years patents. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat., 33: 247-263.

- Simarro, P.P., G. Cecchi, J.R. Franco, M. Paone and A. Diarra et al., 2015. Monitoring the progress towards the elimination of gambiense human African trypanosomiasis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis., 9.

- Musa, A.D., S.T. Dorgu, C. Ogbiko, J. Ikko, M.H. Shuaib, O.F.C. Nwodo and P. Krastel, 2020. Antibacterial investigation using spectrophotometric assay of the polar leaf extracts of Ficus capensis (Moraceae). Asian Pac. J. Health Sci., 7: 23-26.

- Owolabi, A.O., J.A. Ndako, S.O. Owa, A.P. Oluyori, E.O. Oludipe and B.A. Akinsanola, 2022. Antibacterial and phytochemical potentials of Ficus capensis leaf extracts against some pathogenic bacteria. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res., 6: 382-387.

- Musa, D.A., L. Dim-Gbereva, C. Ogbiko and O.F.C. Nwodo, 2019. Phytochemical and in vitro anti-typhoid properties of leaf, stem and root extracts of Ficus capensis (Moraceae). J. Pharm. Bioresour., 16: 165-172.

- Mahmoud, A.B., O. Danton, M. Kaiser, S. Khalid, M. Hamburger and P. Mäser, 2020. HPLC-based activity profiling for antiprotozoal compounds in Croton gratissimus and Cuscuta hyalina. Front. Pharmacol., 11.

- Herbert, W.J. and W.H.R. Lumsden, 1976. Trypanosoma brucei: A rapid “matching” method for estimating the host's parasitemia. Exp. Parasitol., 40: 427-431.

- Nawaz, H., M.A. Shad, N. Rehman, H. Andaleeb and Najeeb Ullah, 2020. Effect of solvent polarity on extraction yield and antioxidant properties of phytochemicals from bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) seeds. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci., 56.

- Jibhkate, Y.J., A.P. Awachat, R.T. Lohiya, M.J. Umekar, A.T. Hemke and K.R. Gupta, 2023. Extraction: An important tool in the pharmaceutical field. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch., 10: 555-568.

- Sultana, B., F. Anwar and M. Ashraf, 2009. Effect of extraction solvent/technique on the antioxidant activity of selected medicinal plant extracts. Molecules, 14: 2167-2180.

- Lahare, R.P., H.S. Yadav, Y.K. Bisen and A.K. Dashahre, 2021. Estimation of total phenol, flavonoid, tannin and alkaloid content in different extracts of Catharanthus roseus from Durg District, Chhattisgarh, India. Scholars Bull., 7: 1-6.

- Terzic, M., S. Fayez, N.M. Fahmy, O.A. Eldahshan and A.I. Uba et al., 2024. Chemical characterization of three different extracts obtained from Chelidonium majus L. (Greater celandine) with insights into their in vitro, in silico and network pharmacological properties. Fitoterapia, 174.

- Badawy, A.A.B., 1972. The effects of salicylate on the activity of rat liver tyrosine-2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. J., 126: 347-350.

- Bero, J., V. Hannaert, G. Chataigné, M.F. Hérent and J. Quetin-Leclercq, 2011. In vitro antitrypanosomal and antileishmanial activity of plants used in Benin in traditional medicine and bio-guided fractionation of the most active extract. J. Ethnopharmacol., 137: 998-1002.

- Oloruntola, D.A., E.O. Dada and M.K. Oladunmoye, 2021. The in vitro antitrypanosomal activity of Albizia gummifera leaf extracts. Open Vet. Sci., 2: 33-39.

- Obeng, A.W., Y.D. Boakye, T.A. Agana, G.I. Djameh, D. Boamah and F. Adu, 2021. Anti-trypanosomal and anthelminthic properties of ethanol and aqueous extracts of Tetrapleura tetraptera Taub. Vet. Parasitol., 294.

- Atawodi, S.E., 2005. Comparative in vitro trypanocidal activities of petroleum ether, chloroform, methanol and aqueous extracts of some Nigerian Savannah plants. Afr. J. Biotechnol., 4: 177-182.

- Nibret, E. and M. Wink, 2011. Trypanocidal and cytotoxic effects of 30 Ethiopian medicinal plants. Z. Naturforsch. C, 66: 541-546.

- Mbaya, A.W., U.I. Ibrahim, O.T. God and S. Ladi, 2010. Toxicity and potential anti-trypanosomal activity of ethanolic extract of Azadirachta indica (Maliacea) stem bark: An in vivo and in vitro approach using Trypanosoma brucei. J. Ethnopharmacol., 128: 495-500.

- Hu, Z., J. Wahl, M. Hamburger and A. Vedani, 2016. Molecular mechanisms of endocrine and metabolic disruption: An in silico study on antitrypanosomal natural products and some derivatives. Toxicol. Lett., 252: 29-41.

- Madaki, F.M., A.Y. Kabiru, A. Mann, A. Abdulkadir, J.N. Agadi and A.O. Akinyode, 2016. Phytochemical analysis and in-vitro antitrypanosomal activity of selected medicinal plants in Niger State, Nigeria. Int. J. Biochem. Res. Rev., 11.

- Ibrahim, M.A., A. Mohammed, M.B. Isah and A.B. Aliyu, 2014. Anti-trypanosomal activity of African medicinal plants: A review update. J. Ethnopharmacol., 154: 26-54.

- Musa, D.A., A. Musa and O.F.C. Nwodo, 2018. Acute and sub-chronic toxicity screening of chloroform extract of Ficuscapensis in rats. J. Phytochem. Biochem., 2.

- Eluka, P., F. Nwodo, P. Akah and C. Onyeto, 2015. Anti-ulcerogenic and antioxidant properties of the aqueous leaf extract of Ficus capensis in Wistar albino rats. Med. Med. Sci., 3: 22-26.

- Ibe, O.E., G.C. Akuodor, M.O. Elom, E.F. Chukwurah, C.E. Ibe and A. Nworie, 2022. Protective effects of an ethanolic leaf extract from Ficus capensis against phenylhydrazine induced anaemia in Wistar rats. J. Herbmed Pharmacol., 11: 483-489.

How to Cite this paper?

APA-7 Style

Musa,

D.A., Asogwa,

S.C., Aigboeghian,

E.A., Ajibodun,

O.A., Raji,

M.O. (2025). Antitrypanosomal Activity and Safety Evaluation of Ficus capensis Leaf Extracts in Mice Infected with Trypanosoma brucei. Trends in Pharmacology and Toxicology, 1(2), 150-158. https://doi.org/10.21124/tpt.2025.150.158

ACS Style

Musa,

D.A.; Asogwa,

S.C.; Aigboeghian,

E.A.; Ajibodun,

O.A.; Raji,

M.O. Antitrypanosomal Activity and Safety Evaluation of Ficus capensis Leaf Extracts in Mice Infected with Trypanosoma brucei. Trends Pharm. Toxicol. 2025, 1, 150-158. https://doi.org/10.21124/tpt.2025.150.158

AMA Style

Musa

DA, Asogwa

SC, Aigboeghian

EA, Ajibodun

OA, Raji

MO. Antitrypanosomal Activity and Safety Evaluation of Ficus capensis Leaf Extracts in Mice Infected with Trypanosoma brucei. Trends in Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2025; 1(2): 150-158. https://doi.org/10.21124/tpt.2025.150.158

Chicago/Turabian Style

Musa, Dickson, Achimugu, Spencer Chibueze Asogwa, Egbenoma Andrew Aigboeghian, Olufemi Anthony Ajibodun, and Mohammed Olumide Raji.

2025. "Antitrypanosomal Activity and Safety Evaluation of Ficus capensis Leaf Extracts in Mice Infected with Trypanosoma brucei" Trends in Pharmacology and Toxicology 1, no. 2: 150-158. https://doi.org/10.21124/tpt.2025.150.158

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.